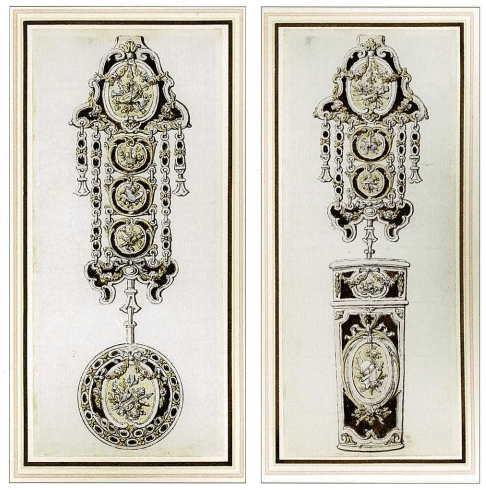

By the 18th century onwards, a pocket watch would be an essential accessory for women and would often be worn attached to a chatelaine or hanging from a waist girdle. Not only were these items functional, but they were also items of adornment, crafted with the same care and elaborate designs as jewellery pieces. 'The main form of attachment of watches for women for most of the 18th century was the equipage' (Source 1). This was an accessory hung from the waist by a large flat hook that would tuck behind the waist fabric of a dress. Equipages consisted of a series of decorated, hinged panels or chains. In the late 18th to early 19th centuries, they were often worn as a set of two; one holding a pocket watch and the other an elongated box which could be used to carry important household objects such as sewing sets (Source 2). The name chatelaine would later be applied to all such devices and would become more elaborate as the 19th century progressed. The name chatelaine did not come into use until 1828, when the French magazine The World of Fashion declared a new fashion accessory 'La Chatelaine' (Source 1).

This pocket watch and watch chatelaine is elaborately decorated with rose, yellow, green gold and platinum. The chatelaine is constructed from three hinged panels with a suspended Albert catch to attach the pocket watch. The chatelaine and the pocket watch case have been elaborately decorated with layered imagery that offer clues into the sentiment behind the piece.

Original hand-coloured 18th century engravings of designs for a matching watch and 'chatelaine' and an equipage. Not signed but attributed to Jean Michel Moreau.

From the 1770's onwards the movement of Romanticism influenced fashion, design, art, music and literature. This movement gained further momentum in France as a response to The French Revolution, whilst also influencing arts and culture in Britain. The values underpinning the movement were based on the ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity, expressed throughout the revolution. These shared ideals of a society based in freedom, equality and companionship saw an emphasis placed on personal relationships and individual thought. These principles were reflected in jewellery design by a strong use of allegory and sentimentalism.

The case of the pocket watch is designed with a torch of love crossed with a bow and quiver full of arrows. The panels of the chatelaine features another bow and quiver and courting doves. The symbolism used throughout art during this period often reflected either worldly or religious belief. The hymeneal torch is a reference to the God of Hymenaeus, the Greek and Roman god of marriage, who is often depicted holding a lit torch. The torch came to represent life, particularly when depicted with doves or courting birds (Source 3). The symbolism of broken or upside-down torches has also been used across funerary art of the time, to represent a life cut short. References can also be observed in literature of the time; the line in William Blake's poem To The Evening Star published in 1783, reads 'thy bright torch of love; thy radiant crown' (Source 4). A modern idiom for the sentiment is the reference to carry a torch for someone, in reference to holding romantic feelings for a person.

The torch of love when crossed with a bow and quiver full of arrows takes on another layered meaning. The bow and quiver are also a reference from Greek and Roman culture as it was used in art to represent, Cupid or Eros, the gods of love. When depicted separately they can represent the beginning of love, as the arrow is Cupid's instigator. However, in the context of many arrows depicted in a quiver, the reference is for the wish of many children. This reference is of biblical origins from psalm 127:3-5.

'Behold, children are a heritage from the Lord, the fruit of the womb is a reward.

Like arrows in the hand of warrior, so are the children of one's youth.

Happy is the man who has his quiver full of them; they shall not be ashamed but shall speak with their enemies in the gate'.

Courting or paired doves have long been a symbol of marriage and are an early Christian iconography. The inclusion of doves in this piece makes clear the designer's messaging. The torch of love, bow and quiver and courting doves read as a message of a happy life filled with marriage and children. This piece could have been gifted to a lady as a wedding present or as a highly romantic gesture by a suitor.

The symbolism used throughout the decoration of this piece is a fantastic example of the sentimentalism that swept through French and British culture from the late 18th century through to the late 19th century. The height of this period is referenced as the Romantic Period (1837-1860) however these sentiments experienced continued popularity right up until the death of Queen Victoria in 1901.

The stem wind pin-set technology of the pocket watch helps to date the piece. The invention of the stem wind pocket watch eliminated the need for the key wind. "The first stem-wind and stem-set pocket watches were sold during the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and the first owners of these new kinds of watches were Queen Victoria and Prince Albert" (Source 5). The invention of the stem wind is credited to Adrien Philippe in 1842 with the first commercial models being produced by Patek Philippe & Co (Source 5). The history of this horological technology dates the pocket watch to the second half of the Victorian era.

This is further supported by the use of green gold in the adornment of the watch case and chatelaine. "Green gold was produced sporadically during the 1800's and mostly in the late 1800's by adding silver as well as cadmium, however the major drawback with cadmium is that it releases toxic fumes when being melted, a problem that was not really known to the jewellers of this period. Due to the danger associated with producing green gold, it only made a very brief appearance in the history of jewellery, however it coincided with a wonderful style at the time which suited its use so well, the Art Nouveau period of the late 1800's to early 1900's" (Source 6). The technology evident in the pocket watch and the use of green gold suggests that the piece dates to the late Victorian to early Edwardian era.

This pocket watch and chatelaine is a great example of how sentiments of the Romantic movement continued to influence jewellery throughout the Victorian era. The technology and materials used within the construction of the piece indicates when the item was made, whilst the imagery used can be decoded to reveal the sentiment behind the piece. This item is currently on display at Kalmar Antiques as part of The Kalmar Vault Collection.

Items of adornment throughout the Georgian era were often utilitarian in nature, with an emphasis not only on aesthetic but on everyday objects of use. Perhaps the most prolific of these items is the pocket watch, which were worn by men and women alike. Jean-Charles Oudin was one of the premiere watch and clock makers of the late 18th century and his brand, Charles Oudin, remains one of the oldest French horology firms still in production today. This pocket watch from The Kalmar Vault is a rare timepiece by the great horologist, Charles Oudin and tells a part of the Parisian watchmaker's history.

The invention of the mainspring in the 16th century revolutionised the horological world and enabled portable timepieces to be created (Source 1). This invention was the catalyst for the creation of pocket watches and carriage clocks, any portable time device. Beyond this invention there is a single name that is attributed to many fundamentals of watch making, Abraham-Louis Breguet. Breguet inventor of the tourbillon, Breguet hairspring and stylistic accents such as Breguet hands and numerals; these technological advancements and design principles defined Breguet's watches and cemented his name as one of the most important figures in the world of horology (Source 1). The legacy of Abraham-Louis Breguet was carried forth by those who apprenticed under him, who learned the skill of watch making by a Master, his most famous apprentice was Charles Oudin.

Charles Oudin grew up in the Northwest of France and was born to a family of watch and clock makers. Charles Oudin was the third generation of horologists in his family with his great uncle, Jospeh Arnould, an established clockmaker in Nancy and his grandfather, Jean-Baptiste Oudin, a clockmaker from Sedan. His Uncle, Charles Oudin known as Oudin Père, was a clock and watchmaker in the place de la Halle in Sedan and was one of the family members who worked for Breguet. His four sons were also in the watchmaking trade and one of them, Jospeh Oudin, worked alongside his cousin, Jean-Charles Oudin for Breguet.

Jean-Charles Oudin apprenticed under Breguet in the late 18th century and worked alongside him at his Parisian studio, he became known within the industry as Charles Oudin. His earliest watches from around 1797 bear the signature, 'Charles Oudin, Elève de Breguet', translating to 'Charles Oudin, pupil of Breguet' (Source 2). "The Oudin name is also often linked to that of the renowned clockmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747-1823) since at least three members of this remarkable family made important contributions to Breguet's oeuvre, especially during the period that Breguet spent in Switzerland during the Reign of Terror, from 1793 to 1795" (Source 3). Charles Oudin remained in Paris during the French Revolution and it is rumoured that Breguet had asked him to continue the running of his studio during his time in Switzerland. However, it was decided by Oudin that he would instead open his own watchmaking firm.

Oudin went on to set up his own studio at the end of the 18th century. "The rarity of the mechanism, the ambition for excellence and the expert know-how: these attributes can just about give the essence of the work of Charles Oudin, one of the oldest French watchmakers who dedicated his life to mastering precision watches" (Source 2). In March 1801, Charles Oudin rented a property at no 65 Palais Royal, at Galerie de Pierre. He had married Anne Antoinette Virginie Le Roy, whose family founded the prestigious Parisian clockmaker firm Leroy. "Oudin quickly gained so much notoriety that in 1805 he created a 'tact repeater' watch for Empress Josephine, the first of a long line of royals who would call upon his services. During his career, Charles Oudin would use his talent to satisfy the desires of Queen Victoria, the Count of Adhémar, the King of Spain, the Tsar of Russia, and even Napoleon III" (Source 2).

This led to a string of achievements including an honourable mention at the 1806 Exhibition for French Industry (Exposition des Produits de l'Industrie Française) for a self-winding watch and clock with moon phase and calendar month indications. "It is those of 1806 and 1819 which earned him, respectively, a medal for a watch winding up by the pendant and a citation for an ingenious equation watch" (Source 2). In 1809, Oudin would open a new shop at no 52 Palais Royal, the address which appears on many of Oudin's watch dials. A mosaic with the firm's name and title "Watch Maker of the French Navy" (Horloger de la Marine Française) appears on the present site today (Source 3).

Exciting elements of this history can be noted on this Charles Oudin pocket watch made in 1830. The pocket watch features a striking monochromatic design with the case constructed in ebony and contrasted with white enamel. The front of the case features roman numerals with a demi-hunter design so that the time can still be read when the case is closed. When the case is opened, Arabic numerals on the dial are revealed in an elegant font. The white enamel dial is in immaculate condition and is signed 'Ch. Oudin Breveté' which translates to 'Ch. Oudin Patent' and bears the retail address 'Palais-Royal 52'. The hands are all original and are turned by the finger to set the time. The key is made from ebony and sterling silver and has a small ratchet system that when winding the pocket watch will turn one way and wind back the other, making it very easy to wind without removing the key from the hole. The watch is attached to an exquisite sterling silver chatelaine, which would have been attached to a pocket or waist band. The back of the case features a detailed sterling silver monogram of the letters 'R' and 'M' bearing a special connection to the original owner.

This piece is such an important piece of horological history from one of the most celebrated watch and clock makers. Timepieces of Charles Oudin can be found across institutions including the Met Museum, the British Museum, the Hermitage, the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva and the Breguet Museum in Paris. We are so lucky to have our own Charles Oudin pocket watch as a part of The Kalmar Vault collection. This item is not for sale but on public display at our store in the Queen Victoria Building.

Sources:

2. Simonin, L (2022), Charles Oudin: the equation of time; Barnebys Magazine: Charles Oudin: The Equation of Time | Barnebys Magazine

3. Richard Redding Antiques (2023), Charles Oudin; Charles Oudin, A late nineteenth century French petite carriage clock of eight day duration by Charles Oudin, Paris, date circa 1880-90 | Richard Redding Antiques

4. Charles Oudin (2023); Women’s Luxury watchmaker 8 place Vendôme (oudin.com)

Patches worn on the face were a curious fashion trend of the Georgian era. These beauty patches or 'mouches' were popular across Europe throughout the 16th and early 17th centuries. Beauty patches were often small pieces of black velvet, silk or satin that had been cut into shapes. Initially, these artificial beauty marks were a peculiarly French phenomenon, but as the country cemented itself as the leader of European fashion, the rage for beauty patches spread beyond its borders (Oatman-Sanford, 2017).

The wearing of these patches was considered fashionable but were also a great way to hide spots, blemishes or scarring on the skin (Curzon, 2021). Smallpox affected perhaps a quarter of the population and left unsightly facial scarring; therefore, patches were an effective way to easily cover these markings (Rendell, 2014). Other venereal diseases that were treated by mercury would also cause facial disfigurement and were often associated with the work of harlots (Rendell, 2014). Therefore, the wearing of beauty patches could be seen across two distinct groups. The sex workers of the lower classes or in the exaggerated fashions of the elite classes as decoration to emphasize painted white skin.

Patches worn for fashion were contrasted with a white complexion often accentuated by make-up. This represented being a part of high society as darker complexions were associated with working outdoors in the sun (Rendell, 2014). Amongst the elite classes the wearing of beauty patches took on new meaning with a coded language developing relating to the placement on the face. These coded meanings could be symbols of flirtation and courtship or could even relate to political allegiances. In England, a Tory would wear a patch on the right side of the face, whilst their political opponents, Whigs, would wear one on the left (Curzon, 2021). A lady could wear a heart shaped patch on her left cheek if she were engaged or the right if she were married. A patch worn beside the eye could indicate passion or one on the nose could be flirtatious (Oatman-Sanford, 2017). There were many different ways which beauty patches were worn in high society to create intrigue and allure.

To facilitate this beauty trend, boxes to carry these patches were made for the home and smaller portable ones were also created. The larger patch boxes may also have compartments for jewellery and would sit on a ladies' or gents' dresser. The portable ones were made to be carried easily in a pocket and would contain a layer of fabric inside. Beauty patches were usually applied with saliva which would adhere to the dense layer of make-up. However, they would often need reapplying throughout the day and therefore a portable box containing fresh patches would be warranted.

This patch box is made from ivory and inlayed with gold. It has the original owner's monogram 'F.M' applied to the side. This would have fitted easily into the pocket of a gentleman's waistcoat or lady's skirt.

This item is on permanent display as part of The Vault Collection at Kalmar Antiques.

Curzon, Catherine (21 Oct, 2021) '7 weird and wonderful Georgian beauty treatments'

Rendell, Mike (21 July 2014) 'Make-up in the 18th century - a fatal attraction'

Paste jewellery offers us incredible insight into the opulence of the Georgian era. Diamonds had dominated the fashions of the aristocratic classes, with their ability to sparkle brilliantly by candlelight. The taste for Rococo style meant that the larger and more elaborate jewellery designs were sought after to dazzle audiences at the many festivities and balls. Luxuries were reserved for the elite classes and extravagant jewels were unattainable to the lower classes of feudal Britain and France. However, such ostentatious displays of wealth led to many opportunistic crimes committed in desperation by the lower-class citizens. Highway robberies became a common and dangerous occurrence for the elite aristocrats who often travelled by carriage at night between festivities.

The invention of paste gemstones answered the needs of the emerging middle classes of Europe and of the aristocratic partygoers of high society. Paste is a term given to imitation gemstones that are made from glass. The production of glass stones had been underway in Venice for many centuries, however, these glass imitations were molded and lacked the sparkle of real gemstones (5.1). It wasn't until 1675 that English glassmaker, George Ravenscroft, developed a version of flint glass that contained a high lead content. This version had high dispersion and a higher refractive index than molded glass or rock crystal and was hard enough to withstand faceting and polishing (5.2). This version was met with widespread popularity across England and thrived for the next 200 years.

Parisian jeweller, George Frederic Strass, continued to pioneer the invention of paste jewellery and in the 1720's he created a superior material that would become synonymous with the trade of paste jewellery. "His shop on the Quai des Orfevres was the most famous paste jewellers, with pieces designed in the latest fashions and set in silver with as much care as if they were diamonds" (3.2). Strass's version was polished with metal powder to create a higher brilliance to the stones, making them a convincing imitation to diamonds, particularly when worn in the nighttime in the flickering candlelight. The popularity of Strass's version of paste jewellery become so significant that he was appointed jeweller to the French Crown. This recognition led to paste jewellery in France being referred to as strass jewellery.

Another popular substitute of the time were rhinestones. In modern times, we associate rhinestones as a part of costume jewellery, however, rhinestones in their truest form refers to rock crystal of a specific geographical origin. Rock crystal from the Rhine (Rhein) River in Germany were cut, faceted and polished to create a colourless gemstone substitute for diamond. The term rhinestone is indicative of this geographical origin, however, throughout history the term was widely applied to rock crystal from other locations and then later to glass or even plastic versions.

This Georgian era portrait miniature brooch and pendant is crafted in silver with rhinestones set into the border. The woman in the portrait is portrayed in Regency era garb with a black choker ribbon and feather headdress. The ribbon motif at the top of the pendant was also common during Georgian era jewellery.

Georgian era paste jewellery allowed for the developing middle class to participate in the opulent fashions of the time but at a price point which they could afford to pay. For the elite classes, they were able to have jewellery pieces made to keep up with current fashions, without having to remodel their family jewels. A trend also developed to have expensive jewellery pieces recreated using paste stones. This was implemented by the elite classes and even the royal families, as it allowed them to wear their jewellery to events without the fear of having them stolen by highway robbers.

Paste jewellery is now highly collectable as they serve as rare examples of designs from the Georgian era. These are sort after as many jewels from this era were remodelled or destroyed to compete with changing fashions.

These items are currently on display at Kalmar Antiques.

Sources:

Navette Jewellery (29th May 2017) 'History of imitation gemstones: glass and paste', History of Imitation Gemstones – Paste and glass gemstones – navette jewellery

Phillips, Clare (2019) 'Jewels & jewellery'; Thames & Hudson V&A

The sentimental power of hair used in jewellery lies in the contrast of the relic and its absence from the body. It is this contrast, of the relic which remains and the body that is lost, where we are poignantly reminded of a life. This sentiment is most sincere when we consider memorial jewellery exchanged between soldiers and their families. Military conflicts, from a historical perspective, often meant the bodies of fallen soldiers were lost to a foreign land and never returned home. Parents, spouses, children and friends would farewell their loved ones into battle, sometimes with no tangible reminder of their life after passing. It is in these circumstances that the true intimacy that human hair as relic is understood.

This locket is a rare example of the concept of jewellery as material memory. The outside of the locket features beautiful blue enamel work which would have been proudly worn by a loved one. Inside the locket is a lock of hair and inscription which reads;

"Capt. A.A Cartwright Rifle Brigade Fell at Inkermann Nov 5 1854"

This inscription gives us the identity of the personal relic and the circumstances under which they died. This hair belonged to Captain Aubrey Agar Cartwright, with the documentation of his military service commencing with his position as Second Lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade in 1842. He was awarded the South Africa medal for his service in Cape Town and served in the famous battles of Alma, Sebastapol and Balaklav. He lost his life at age 29 on the 5th of November 1854 at the Battle of Inkerman in the Crimean War. "The Battle of Inkerman saw fierce fighting hampered by thick fog, resulting in poor communication between the troops. Casualties were disproportionately high" (Royal Collection Trust, 2016).

We see Captain Cartwright's death recorded below in the Rifle Brigade Chronicles next to the November 5th date entry.

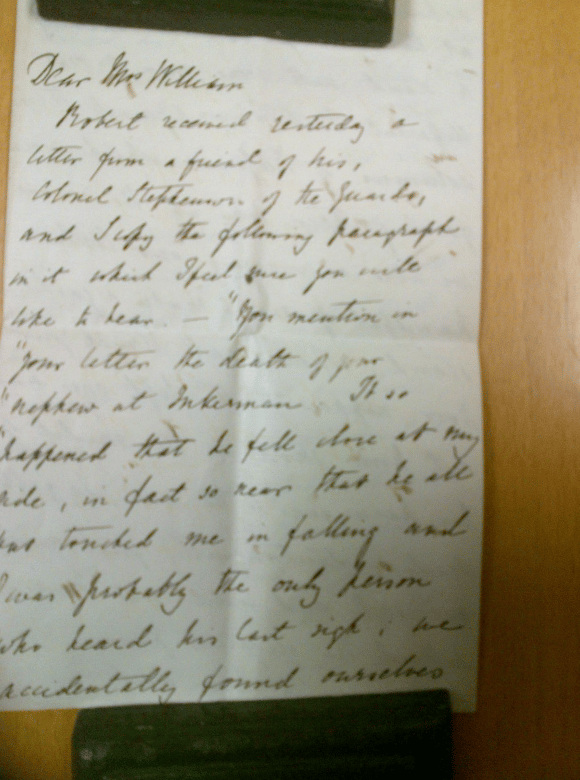

From these military records we see the death of Capt. Cartwright recorded in a strictly factual manner. It is the material history of the locket, which gives us an emotional understanding of Aubrey Cartwright's life. Aubrey was unmarried and left behind his parents, Mary Anne Cartwright and William Cartwright, and siblings. The Cartwrights were an aristocratic family of Northamptonshire and owned a large amount of property in the district on Aynho, including Aynhoe Park - a country estate occupied by the Cartwright family for over three-hundred years. Detailed archives pertaining to the Cartwright family are kept at the National Archives. These records include detailed letters written by Aubrey Cartwright during his active service. The most poignant of these documents includes a handwritten letter from a fellow serviceman addressed to a Mr. William detailing the passing of Aubrey Cartwright in battle;

"It so happened that he fell close at my side, in fact so near that he... [undecipherable]... me in falling and I was probably the only person who heard his last sigh" (extract partially transcribed from letter).

Locks of Aubrey Cartwright's hair were sent at different times to his family. Aubrey enclosed a lock of his own hair in a letter to his mother, from his time spent in Alma. There is another lock of Aubrey's hair in the archive labelled "Mr. Cartwright hair removed from bullet". Through these archives we gain a sense of Aubrey Cartwright's acute awareness of the fact that his family may require a physical memento of his. From the Georgian era and throughout the Victorian era, the gifting of hair as keepsake was common practice. It is sorrowful to see that the hair enclosed in these letters eventually served their intended purpose, to be used as a personal keepsake of Aubrey Cartwright's life upon his death. We can make connections that the hair enclosed in letters to his parents and the additional fact of Aubrey being unmarried, lead to suggest that the locket would likely have been worn by his mother, Mary Anne Cartwright, in memory of her son lost to war. Further evidence of this is detailed in the meeting notes of the 49th meeting of the Aynho History Society in June 2012 with the below statement.

"Aubrey Agar Cartwright firstly fought at Boem Plaats in South Africa. He was then in the Crimean, which was close, hand-to-hand fighting in freezing conditions, with all the wrong kit in the wrong places. He was at Sevastopol, and then at Inkerman, where he was killed by a shot to the head, aged 29. A lock of his hair was sent back to his parents, and is in the Archive."

The creation of this item with such a detailed inscription and personal relic serves as material memory to the life of Aubrey Agar Cartwright. The emotional purpose of this jewellery item, is to mourn and to bring comfort to the wearer. The creation of this item with such a detailed inscription and personal relic serves as material memory to the life of Aubrey Agar Cartwright. It gives us insight into his life and service and also of the love and loss experienced by those he left behind.

This item is currently on display in our Kalmar Vault Collection at Kalmar Antiques.

Sources:

This mourning ring is the next item in our Kalmar Vault series and from this ring we begin to understand Christian iconography and mourning rituals prevalent at the turn of the 20th century. Pieces such as this one offers us a unique portal into history and to those who came before us. The inscription of this piece reads “Dad died 4th of March 1900" on the inside of the band with the initials inscribed upon the heart at the front of the piece. The intention of this piece is clear in its purpose to serve as a memento of a Father by his family.

To understand the layer of emotion entwined with this mourning ring we must first understand the context of the symbolism chosen to adorn the front of this piece. The front of the ring features the three symbols of Christian virtue including the cross, anchor and heart. These symbols displayed in unison represent faith, hope and charity and have become a common allegory used in jewellery design.

Cathedral dome mural personifying faith, hope and charity. Source: Marywood University

It is important to note that in this context the term charity is interchangeable with the word love. Charity in Christian thought signifies the highest form of love, an unselfish love of ones fellow man based on the reciprocal love between man and God (Britannica, 2022). The mention of these virtues can be found in the Christian writings of St. Paul who, in a letter to the church at Thessalonian as they faced persecution, stated “we remember before our God and Father your work produced by faith, your labor prompted by love, and your endurance inspired by hope in our Lord Jesus Christ" (1 Thessalonians 1:3). The symbolism that would come to represent these virtues was later produced through various art practices with slight changes to the iconography over time.

The heart allegory, signifying charity, was originally depicted as a woman with small children around her but was later adapted to the heart shape in artworks from the late 14th century (Navette Jewellery, 2021). The anchor symbol to represent hope can be traced back to the New Testament Book of Hebrews in the passage “have this hope as an anchor for the soul, firm and secure" (Hebrews 6:18. 19). The anchor as a symbol of hope gained further relevance during the Napoleonic Wars when many men were seafaring and was interpreted as a symbol of hopes of a safe return (Erica Weiner, 2021). The cross is a more obvious signifier of the Christian faith that is still widely used today. We see these three symbols frequently portrayed together across art practices such as tapestry, painting and sculptures in the 17th century. The three virtues can be seen in jewellery design as early as the Georgian era but gained wide popularity in jewellery design from the late 18th century.

The incorporation of the three virtues in this mourning ring can be seen as a direct link to the deceased and their Christian faith. “Theology is one of the primary reasons for the creation of mourning and sentimental jewels, being a key identifier in someone's understanding of the afterlife and their relationship virtues" (Peters, 2022). Therefore, the inclusion of these symbols was a purposeful choice by the person who commissioned the mourning ring, whether that be the family or the deceased person themselves prior to their passing.

The other element of this ring is the hair work detail that is woven around the band. The inclusion of hair in jewellery was common from the Georgian era onwards as sentimental tokens of love and friendship as well as for commemorative purposes. In this particular ring the hair is included as a personal relic from the deceased and has been included as a memento.

The gifting of mourning rings at funerals had become common practice throughout the Victorian era but was particularly prevalent after the death of Prince Albert when Queen Victoria plunged England into an era of high mourning. The influence of the grieving monarch over her nation kick started an industry designed to meet the needs of these strict societal protocols. Standards of dress were to be adhered to after the loss of a loved one and the distribution of mourning rings at funerals was seen as a comment on the class and status of the family. These mourning practices spread across the United States as well as Britain as the Civil War left many grieving families in its wake. Australia was also adhering to these practices with its direct influence as a Commonwealth Nation of Britain. “That people could afford these jewels is even more remarkable, given that producing bespoke rings in volume was not as easy a task as it was in the 19th century, following the use lower grade alloys and machinery development during the Industrial Revolution" (Peters, 2022). The time which this ring was produced was at the turn of the century when societal attitudes were shifting after decades of adhering to the Queen's strict mourning protocols. Mourning practices were on the decline but mourning jewellery was still being mass produced and gifted to loved ones.

This ring gives us insight into the mourning rituals and customs of the Western world during the 19th century to the early 20th century. It provides us with a tangible connection to the deceased and their theological beliefs. These pieces of jewellery were created with the intention that their loved one would be remembered. It is an amazing thought that these pieces have lasted the test of time and that these items and the memory of those which they commemorate endure.

Sources:

Britannica (2022), 'Charity Christian concept', Britannica; https://www.britannica.com/topic/charity-Christian-concept

Erica Weiner (2022), 'Diamond and pearl faith, hope and charity ring', Erica Weiner; https://ericaweiner.com/products/late-victorian-diamond-and-pearl-faith-hope-charity-ring

Navette Jewellery (2021), 'Symbolism in antique jewellery - faith, hope and charity (love)', Navette Jewellery; https://navettejewellery.org/2021/07/07/symbolism-in-antique-jewellery-faith-hope-and-charity-love/

Peters, Hayden (2022), 'Colonial Australian sentimental jewels', Art of Mourning; https://artofmourning.com/colonial-australian-sentimental-jewels/

Peters, Hayden (2022), 'Faith, hope and charity', Art of Mourning; https://artofmourning.com/faith-hope-and-charity/

Antique jewellery is a window into the past lives of those who came before. This piece from the personal collection of the Kalmar's is a perfect encapsulation of how these jewels connect us to a different time, place and person. This item is a vinaigrette case and is layered in both sentiment and purpose. Through the existence of this item, we meet Miss Miriam Isherwood and her aristocratic family whose lives unfolded in the quaint town of Marple, Cheshire.

Upon first glance, you would be forgiven for mistaking this piece as an item of mourning jewellery, created to mark the bereavement of a loved one. The lock of woven hair and the inscription on the reverse side of the locket are common aesthetic elements of mourning jewels. However, upon further inspection it is evident that this item was gifted with another sentiment in mind for the recipient.

The inscription upon the inside lid gifts us insight into the intended sentiment of the piece. The cursive font is so decorative and neatly done that it is hard to believe that it was engraved by hand. Undoubtedly the work of a master engraver, the length and consistency of the message that has been inscribed upon the lid is truly remarkable. With careful inspection we can read the inscription as follows;

“To Mifs Miriam Isherwood,

By the female monitors of the,

Marple Church Sunday School,

A token of respect for her,

Unwearied exertions in,

Promoting the spirituals,

Temporal welfare of new,

Scholars 17 June 1839"

After deciphering the inscription, we begin to understand the circumstance surrounding this jewel and its intended recipient. The beneficiary of the piece was Miriam Isherwood as a token of respect for her work as a Monitor at the Marple Sunday School gifted to her by her colleagues.

Another element that adds to the sentiment of the piece is the inclusion of plaited hair in the locket compartment. During the Victorian era, of which this piece originates, “hair compartments are to be seen on every kind of jewel from this time" (Hinks, 1975). Hair was a common token to be gifted as a token of friendship and love.

“There's different kinds of hair art and there are different purposes; one is for mourning, and then one is for family trees, or friendship keepsakes, so there's different imagery you'll see in those things (Burgess, 2018).

When we consider the circumstances in which this piece was gifted, it is unlikely that the hair contained in the piece is that of Miriam Isherwood. This is a fair assumption as the piece is dated 1839 and records show that Miss Miriam Isherwood passed away in 1870. It is therefore, very unlikely that the gift givers would have had access to Miss Isherwood's own hair. We can speculate that the hair within the piece was that of the gift givers, the female monitors of Marple Church Sunday School, or perhaps even that of the students which Miriam Isherwood offered spiritual guidance. Although we cannot know for sure, a locket containing the hair of her peers or her students as a sentiment of thanks for her service is likely to fit the occasion for which the piece was gifted.

The style of hairwork featured in the piece was created using a palette work technique. “Palette work tends to be for jewellery and larger works, and is a technique where you'll see woven hair in patterns. Clean, flattened hair was woven or mixed with a sap-like material to create a sheet, which was then crafted into shapes that usually goes under glass, or it goes on top of ivory, in jewellery" (Burgess, 2018). Considering the technique, it is possible that the hair enclosed in this piece was that of multiple people that had been worked together in this way.

Jewellery in the Victorian era was renowned for being deeply sentimental but another important aspect of design was utilitarian function. This piece serves as an example of this with the reverse side of the locket being utilised as a vinaigrette. Vinaigrette cases were used to house a perfume-soaked sponge or piece of cotton that could be brought to the nose to mask unpleasant odours. “During the 19th century, vinaigrettes were a fashionable indication of social ranking, as those who were able to afford perfume or concern themselves with their outward appearance at all, were among the elite. Sanitisation standards were low for all including the highest classes, but they were able to compensate with perfume which would distinguish them from the working class" (AC Silver, 2022). Therefore, through this piece we can begin to understand the social ranking of the Isherwood family. A piece such as this would likely have been worn suspended from a chatelaine at Miss Isherwood's waist, a truly thoughtful and useful gift.

This piece not only provides us with Miss Isherwood's name but it connects us to the church in Marple, Cheshire where she received this gift some 183 years ago. Miriam Isherwood was the daughter of John Bradshaw-Isherwood and Elizabeth Bradshaw-Isherwood born in 1816. She was one of seven daughters and one brother who made up the Isherwood clan, a highly respectable family from the quaint town of Marple. The Bradshaw-Isherwood family were one of the most notable families within this region and the lavish Marple Hall has been the ancestral estate to the family for many generations. The Bradshaw-Isherwood family are widely documented for making substantial contributions to the Marple Church and community. As such, it comes as no surprise that a piece such as this, would be gifted to a member of the Isherwood family.

Further research reveals the impact which the aristocratic Isherwood-Bradshaw family have had on the region of Marple and to English history. When tracing the ownership of Marple Hall (pictured right) we see that the family of Miss Miriam Isherwood were descendants of Lord President John Bradshaw, whose father Henry Bradshaw II and older brother Henry Bradshaw III were both noted as Landlords of Marple Hall. John Bradshaw made a significant impact to the history of England with his close political connections to Oliver Cromwell and his appointment as the Lord President of the Council of State. His legacy would be one shrouded in controversy for his role in issuing the warrant for the execution of King Charles I in 1649. When the crown was restored to King Charles II, he condemned the actions of regicide and therefore John Bradshaw can be considered a divisive figure when reviewing English history. Centuries on from their ancestor's tribulations, the Bradshaw family lived in relative obscurity with no other notable endeavours into political life. They appeared by all counts to have lived a life of quiet privilege within the town of Marple and surrounds.

This item, a token of gratitude, connects us to the life of Ms. Miriam Isherwood and her distinguished family ties in Marple, Cheshire. With this tangible connection to the parish of the Marple Church community, we are able to greater understand the local history of this area and also the Bradshaw-Isherwood family. Unfortunately, Miss Isherwood's family home, Marple Hall, is no longer standing with only minor ruins remaining. The Marple Church is still in operation, as is the Sunday School of which Miss Isherwood pioneered.

Sources:

Objects are important as they tell our human history by connecting us to past places and people. These tangible bonds offer us the rare opportunity to touch history. Never has this sentiment rung truer than in the instance of this imperial half pint measuring cup. One of the humbler items in the Kalmar's collection, although it may not be crafted from the highest carat gold or covered with the finest jewels, the unique instrument offers us a direct lineage to our local history. From this measuring cup, the redemption tale of James Blanch, a convict, instrument maker and perhaps Australia's first metrologist unfolds.

James Blanch was born in England in 1784 and at the age of fourteen it is surmised that he was apprenticed in the trade of mathematical instrument making. By the end of the 18th century, London had become the world's leading centre for scientific instrument making with numerous piece-makers and wholesalers specialising in the manufacture of optical, mathematical and philosophical instruments (Holland, 2000). Despite this training, the first recorded occupation of James Blanch was from 1814 as a Customs House Officer working on the London docks. It was during his time working on the docks that opportunity mixed with poor judgement would lead Blanch to commit an act of petty theft. Together with a fellow official, Blanch stole ten yards of Russia Duck, a heavy linen fabric, worth 30 shillings from the ship, Lord Harlington. This misdemeanor would see the pair sentenced and bound for Botany Bay aboard the convict ship which landed on Sydney shores in 1816.

Having served his time in the colony, Blanch gained his Ticket of Leave in 1821 and just one year later, his wife Sarah sailed out on the 'Brixton' to join him. Now open to start his life as a free member of society, Blanch set up his professional trade and established the Sydney Foundry and Engineering Works. “Blanch set up business in Pitt Street as a mathematical and philosophical instrument maker, brass founder, brazier, plater and general worker in silver and brass" (Holland, 2000). He would later move his business to the central location of George Street where he would also acquire further properties. Accompanied by other convicts and an apprentice of his own, Blanch would achieve reasonable success with his business whilst supporting his growing family. However, it would be the 'Bill for preventing the use of false and deficient Weights and Measures' passed in August 1832 that would forever weave the work of James Blanch into our country's history.

It was accountant and mathematician, Patrick Kelly, who first recorded the term of metrology in an 1816 text in which he proposed universal standards, a central remit of discipline, aimed at the development of agreed standards for weights and measures in science and industry (MAAS, 2022). As it stood, “Victorian England and Colonial Australia were awash with interpretations about reliable and agreed standards, and the construction of artefacts to accurately measure them" (MAAS, 2022). It was therefore decided, that with the passing of the new bill the infant colony of New South Wales would develop a uniformed approach to measurement and weight based upon the imperial system of England.

The provision of these items was awarded to James Blanch with the task of creating seven sets of instruments accurately determining weights, volume measurements and a standard yard. The sets were to include the below;

Series of weights: 1, 2, 4, and 8 drams, 1, 2, 4, and 8 ounces, 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 28, and 56 pounds.

Series of volume measures: half gill, gill, half pint, pint, quart, half gallon, gallon, peck, half bushel and bushel.

An instrument the length of one standard yard, better known as a yard stick.

The seven sets were “distributed to police offices in various regional towns - Parramatta, Windsor, Bong-Bong, Goulburn, Bathurst, Maitland - as well as one to the police office in Sydney" (Holland, 2000). These instrument sets would be the foundations of accurate and cohesive measurement units across the colony of New South Wales.

Embossed in the metal of the measuring cup is the maker's mark 'J.Blanch' and the date '1833'. There is another symbol etched into the side of the measuring cup that resembles an arrow. This mark is described as the 'broad arrow' and was used across England and colonial Australia. "Every item made or used by government convicts had to be marked or stamped with a broad arrow, the mark of government property, to prevent theft and the selling-on of government goods and tools. The broad arrow was so widely used to mark objects used by convicts, that it became associated with the convict system itself, rather than just a symbol of government property" (Sydney Living Museums, 2022). At the time of this item being commissioned by the government James Blanch was a free member of society. Therefore, a distinction can be made that this mark was associated with the sets belonging to government property as opposed to being included due to Blanch's prior convict status.

From convict to successful businessman and pioneer of engineering practices within Australia, the tale of James Blanch is a true under-dog story. James Blanch passed away in 1841 with multiple properties to his name and is listed at number 182 of all time richest Australians (Past Lives, 2012). His foundry was taken over after his death by Peter Nicol Russell who continued its operation with his two brothers under the company P.N Russell and Company. Peter Nicol Russell would live on to become a pioneering figure of the engineering industry within Australia and was a significant benefactor to the University of Sydney.

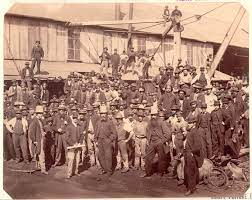

Workers photographed in front of the Sydney Foundry & Engineering Works operated by PN Russell & Co circa 1870-1875

Image source: The State Library of New South Wales Collections

The legacy of James Blanch and his contributions to engineering and instrument making within Australia live on, although they are far less noted than that of his successor. It is through objects such as this imperial half pint measuring cup, which bears his name, that the tale of James Blanch endures. Undoubtedly, there are many objects crafted by the hands of Blanch that would remain scattered across the state of New South Wales and afar, the imperial half pint measuring cup in the private collection of the Kalmar's is but one example of his work. Another is an Imperial half bushel which can be viewed at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney.

Image source: Powerhouse Museum Collections

Sources:

Australian Government National Measurement Institute (2010), 'History of Measurement in Australia'; 'History of Metric Conversion', www.measurement.gov.au/measurementsystem/Pages/HistoryofMeasuremtin

Holland, Julia (2000), 'James Blanch - Australia's first meterologist?'; The Australian Metrologist, http://members.optusnet.com.au/jph8524/JHjames_blanch.htm

Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences (2022), Imperial half bushel measure; Powerhouse Museum Collection, https://collection.maas.museum/object/550907

Past Lives (2012), 'James Blanch (1784 -1841): custom house officer, convict, and mathematical instrument maker', https://mprobb.wordpress.com/2012/03/23/james-blanch-1754-1841-custom-house-officer-convict-and-mathematical-instrument-maker/

State Library of New South Wales (2022), 'Fanny voyage to New South Wales, Australia in 1815 with 175 passengers'; Convict Records, https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/fanny/1815

Sydney Living Museums (2022), 'Branding iron early to mid 19th century'; Objects Records, https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/taxonomy/term/18636#object-107796

To kickstart The Kalmar Vault series we begin with two significant pieces of Australian jewellery history. From the Kalmar's private collection comes a fantastic pocket watch and Albert chain from acclaimed jeweller and watchmaker, Mr. Henry F Hutton. "The business founded by Henry Hutton around 1880 became one of the premier retail jewellery establishments in Ballarat, Victoria" (Cavill, Cocks & Grace: 1992). The town of Ballarat in Victoria was one of Australia's most significant gold mining towns during the mid-19th century. The gold rush saw prospectors migrate to towns such as Bathurst, Buninyong and Ballarat. This brought an influx of many Colonial jewellers who settled and set up businesses in the towns. Hutton worked out of his shopfront on Stuart Street in the second half of the 19th century between the 1880s to late 1950s. It was there that Hutton gained notoriety for his quality jewellery and skilled watchmaking.

Although the Kalmar's have owned other pieces of Hutton's work this exceptional Albert chain and pocket watch is a piece which remains in their private collection. “Because of its great rarity, Australian jewellery of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is now eagerly sought after by collectors and museums alike"(Schofield, A & Fahy, K: 1990). The pieces are not only of exceptional quality but have fantastic significance to Australia's history.

The Albert Chain: Albert chains were originally created for the purpose of fastening a pocket-watch to a men's waistcoat. Named after the style of watch chain worn by Prince Albert the chain traditionally comprised of a T-bar at one end that would affix to a buttonhole and a swivel hook at the other to attach to the pocket watch. This Albert chain is of this traditional design but with exceptionally ornate detailing.

“One thing which distinguishes Australian jewellery of the mid-nineteenth century is its generous use of gold which was so abundant. Australian gold watch chains, based closely on the type made popular in England by Prince Albert, are usually much heavier than the English ones: the same principle applies to Australian gold fob seals and brooches" (Schofield, A & Fahy, K: 1990).

Crafted in 18ct yellow gold the piece features two twisted chains held in place with two sliding mechanisms. At the end of the chain hangs the traditional T-Bar and ornate chain tassel. Each surface of the gold has incredible hand-engraved details which feature beautiful floral patterns. A Hutton maker's mark can be found embossed on the bottom bail of the chain.

The Pocket Watch: The pocket watch case, also crafted in 18ct yellow gold, features exceptional detailing on either side. On one side, a shield with an ornate wreath of floral and filigree engraving surrounding it. The other side, features the same wreath pattern but with a bouquet of flowers in the center. The watch-face is also decorated with floral designs and roman numerals upon the dial. Sitting underneath the centre twelve are the words “Henry F. Hutton Ballaarat, this is interesting as it not only depicts the maker's name but also the traditional spelling of the city, which later dropped the additional 'A' from its title.

These two incredible pieces of Australian history are such fantastic examples of the quality of work being produced by Australian jewellers throughout the 19th century. Many pieces of jewellery from this era tell the history of our country, from the gold rush, colonization, societal changes and the appreciation of native flora and fauna. To find out more about other significant Australian jewellers read a brief history of Australian jewellery.

Shop Antique Australian Jewellery

Sources: