Objects are important as they tell our human history by connecting us to past places and people. These tangible bonds offer us the rare opportunity to touch history. Never has this sentiment rung truer than in the instance of this imperial half pint measuring cup. One of the humbler items in the Kalmar's collection, although it may not be crafted from the highest carat gold or covered with the finest jewels, the unique instrument offers us a direct lineage to our local history. From this measuring cup, the redemption tale of James Blanch, a convict, instrument maker and perhaps Australia's first metrologist unfolds.

A Convict's Tale

James Blanch was born in England in 1784 and at the age of fourteen it is surmised that he was apprenticed in the trade of mathematical instrument making. By the end of the 18th century, London had become the world's leading centre for scientific instrument making with numerous piece-makers and wholesalers specialising in the manufacture of optical, mathematical and philosophical instruments (Holland, 2000). Despite this training, the first recorded occupation of James Blanch was from 1814 as a Customs House Officer working on the London docks. It was during his time working on the docks that opportunity mixed with poor judgement would lead Blanch to commit an act of petty theft. Together with a fellow official, Blanch stole ten yards of Russia Duck, a heavy linen fabric, worth 30 shillings from the ship, Lord Harlington. This misdemeanor would see the pair sentenced and bound for Botany Bay aboard the convict ship which landed on Sydney shores in 1816.

Having served his time in the colony, Blanch gained his Ticket of Leave in 1821 and just one year later, his wife Sarah sailed out on the 'Brixton' to join him. Now open to start his life as a free member of society, Blanch set up his professional trade and established the Sydney Foundry and Engineering Works. “Blanch set up business in Pitt Street as a mathematical and philosophical instrument maker, brass founder, brazier, plater and general worker in silver and brass" (Holland, 2000). He would later move his business to the central location of George Street where he would also acquire further properties. Accompanied by other convicts and an apprentice of his own, Blanch would achieve reasonable success with his business whilst supporting his growing family. However, it would be the 'Bill for preventing the use of false and deficient Weights and Measures' passed in August 1832 that would forever weave the work of James Blanch into our country's history.

The Measure of a Man

It was accountant and mathematician, Patrick Kelly, who first recorded the term of metrology in an 1816 text in which he proposed universal standards, a central remit of discipline, aimed at the development of agreed standards for weights and measures in science and industry (MAAS, 2022). As it stood, “Victorian England and Colonial Australia were awash with interpretations about reliable and agreed standards, and the construction of artefacts to accurately measure them" (MAAS, 2022). It was therefore decided, that with the passing of the new bill the infant colony of New South Wales would develop a uniformed approach to measurement and weight based upon the imperial system of England.

The provision of these items was awarded to James Blanch with the task of creating seven sets of instruments accurately determining weights, volume measurements and a standard yard. The sets were to include the below;

Series of weights: 1, 2, 4, and 8 drams, 1, 2, 4, and 8 ounces, 1, 2, 4, 7, 14, 28, and 56 pounds.

Series of volume measures: half gill, gill, half pint, pint, quart, half gallon, gallon, peck, half bushel and bushel.

An instrument the length of one standard yard, better known as a yard stick.

The seven sets were “distributed to police offices in various regional towns - Parramatta, Windsor, Bong-Bong, Goulburn, Bathurst, Maitland - as well as one to the police office in Sydney" (Holland, 2000). These instrument sets would be the foundations of accurate and cohesive measurement units across the colony of New South Wales.

Embossed in the metal of the measuring cup is the maker's mark 'J.Blanch' and the date '1833'. There is another symbol etched into the side of the measuring cup that resembles an arrow. This mark is described as the 'broad arrow' and was used across England and colonial Australia. "Every item made or used by government convicts had to be marked or stamped with a broad arrow, the mark of government property, to prevent theft and the selling-on of government goods and tools. The broad arrow was so widely used to mark objects used by convicts, that it became associated with the convict system itself, rather than just a symbol of government property" (Sydney Living Museums, 2022). At the time of this item being commissioned by the government James Blanch was a free member of society. Therefore, a distinction can be made that this mark was associated with the sets belonging to government property as opposed to being included due to Blanch's prior convict status.

An Instrumental Legacy

From convict to successful businessman and pioneer of engineering practices within Australia, the tale of James Blanch is a true under-dog story. James Blanch passed away in 1841 with multiple properties to his name and is listed at number 182 of all time richest Australians (Past Lives, 2012). His foundry was taken over after his death by Peter Nicol Russell who continued its operation with his two brothers under the company P.N Russell and Company. Peter Nicol Russell would live on to become a pioneering figure of the engineering industry within Australia and was a significant benefactor to the University of Sydney.

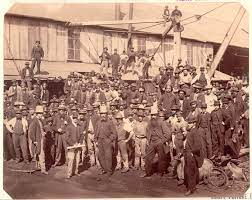

Workers photographed in front of the Sydney Foundry & Engineering Works operated by PN Russell & Co circa 1870-1875

Image source: The State Library of New South Wales Collections

The legacy of James Blanch and his contributions to engineering and instrument making within Australia live on, although they are far less noted than that of his successor. It is through objects such as this imperial half pint measuring cup, which bears his name, that the tale of James Blanch endures. Undoubtedly, there are many objects crafted by the hands of Blanch that would remain scattered across the state of New South Wales and afar, the imperial half pint measuring cup in the private collection of the Kalmar's is but one example of his work. Another is an Imperial half bushel which can be viewed at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney.

Image source: Powerhouse Museum Collections

Sources:

Australian Government National Measurement Institute (2010), 'History of Measurement in Australia'; 'History of Metric Conversion', www.measurement.gov.au/measurementsystem/Pages/HistoryofMeasuremtin

Holland, Julia (2000), 'James Blanch - Australia's first meterologist?'; The Australian Metrologist, http://members.optusnet.com.au/jph8524/JHjames_blanch.htm

Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences (2022), Imperial half bushel measure; Powerhouse Museum Collection, https://collection.maas.museum/object/550907

Past Lives (2012), 'James Blanch (1784 -1841): custom house officer, convict, and mathematical instrument maker', https://mprobb.wordpress.com/2012/03/23/james-blanch-1754-1841-custom-house-officer-convict-and-mathematical-instrument-maker/

State Library of New South Wales (2022), 'Fanny voyage to New South Wales, Australia in 1815 with 175 passengers'; Convict Records, https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/fanny/1815

Sydney Living Museums (2022), 'Branding iron early to mid 19th century'; Objects Records, https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/taxonomy/term/18636#object-107796