Take a look inside Kalmar Antiques’ private collections. These incredible collections feature jewellery, watches and decorative objects that have been curated by the Kalmar family over the last 30 years and have never been previously available for public display. These collections include rare historical items, poignant sentimental pieces and items of obscurity that capture a bygone era. Visit the permanent display in-store, follow the blog series online or sign up to our newsletter to be the first to know about upcoming articles and exhibitions.

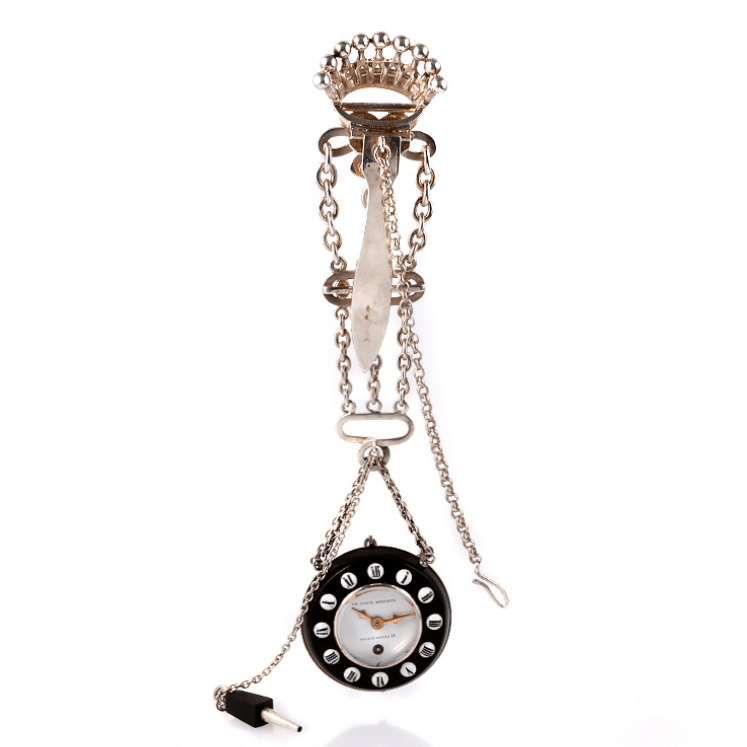

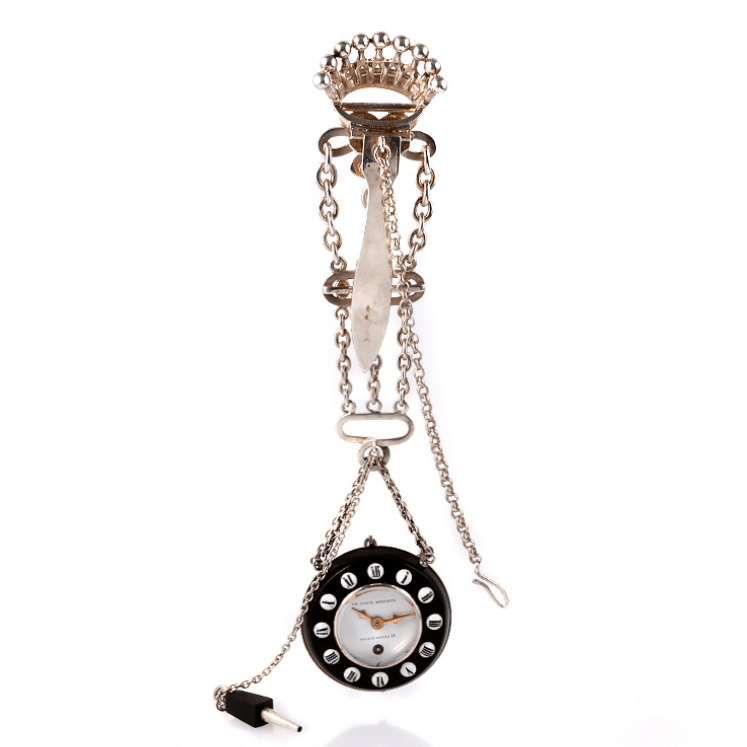

By the 18th century onwards, a pocket watch would be an essential accessory for women and would often be worn attached to a chatelaine or hanging from a waist girdle. Not only were these items functional, but they were also items of adornment, crafted with the same care and elaborate designs as jewellery pieces. 'The […]

Read More

The rule of Mary, Queen of Scots (1542 - 1567) was shrouded in scandal and betrayal which ultimately led to her abdication and subsequent execution. Her rule was documented throughout art history and her portrait is one of the most prolific subjects across portraiture art and jewellery. Mary, Queen of Scots had an affinity for […]

Read More

This item from the Kalmar Vault is a unique piece of 19th century Australian jewellery. Through tracing the history of this item, we uncover the story of the Flavelle brothers and in turn, the origins of jewellery manufacture within colonial Australia. This suite of jewellery is of exceptional quality and showcases the fashions and materials […]

Read More

Items of adornment throughout the Georgian era were often utilitarian in nature, with an emphasis not only on aesthetic but on everyday objects of use. Perhaps the most prolific of these items is the pocket watch, which were worn by men and women alike. Jean-Charles Oudin was one of the premiere watch and clock makers […]

Read More

Patches worn on the face were a curious fashion trend of the Georgian era. These beauty patches or 'mouches' were popular across Europe throughout the 16th and early 17th centuries. Beauty patches were often small pieces of black velvet, silk or satin that had been cut into shapes. Initially, these artificial beauty marks were a peculiarly […]

Read More

Paste jewellery offers us incredible insight into the opulence of the Georgian era. Diamonds had dominated the fashions of the aristocratic classes, with their ability to sparkle brilliantly by candlelight. The taste for Rococo style meant that the larger and more elaborate jewellery designs were sought after to dazzle audiences at the many festivities and […]

Read More

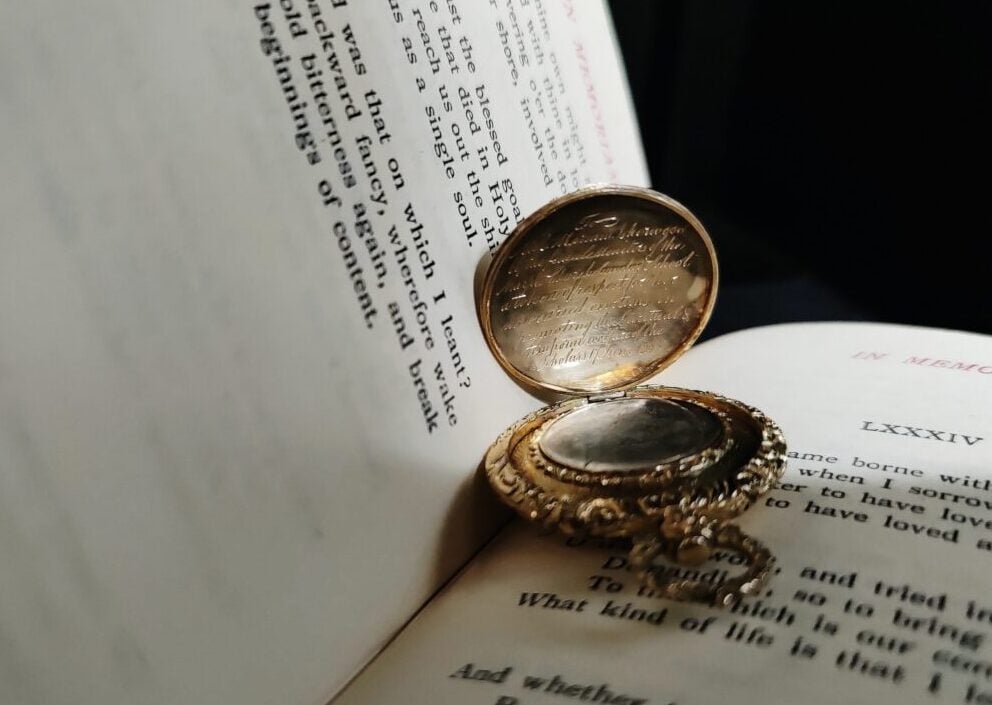

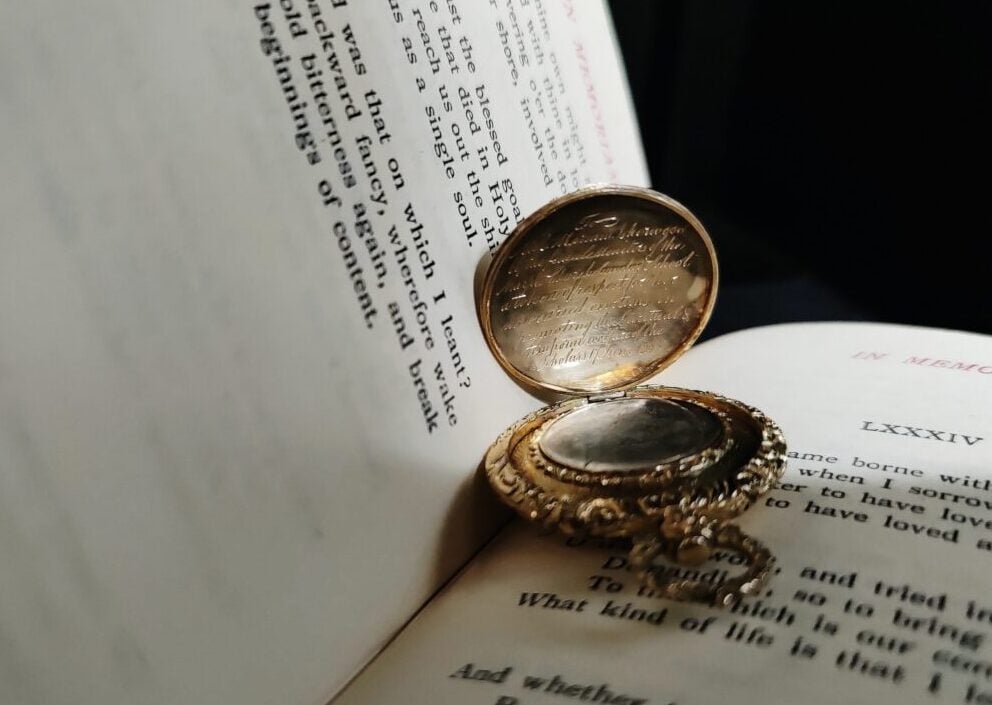

The sentimental power of hair used in jewellery lies in the contrast of the relic and its absence from the body. It is this contrast, of the relic which remains and the body that is lost, where we are poignantly reminded of a life. This sentiment is most sincere when we consider memorial jewellery exchanged […]

Read More

In the Georgian era opulent fashion trends were just as popular for men as they were for women. Men's fashion included breeches, sashes, cravats, hats and decorative buckles for belts and shoes. The elaborate buckles would be fashioned with all types of gemstones and materials from cut steel to diamonds set in gold. The trend […]

Read More

This mourning ring is the next item in our Kalmar Vault series and from this ring we begin to understand Christian iconography and mourning rituals prevalent at the turn of the 20th century. Pieces such as this one offers us a unique portal into history and to those who came before us. The inscription of […]

Read More

Antique jewellery is a window into the past lives of those who came before. This piece from the personal collection of the Kalmar's is a perfect encapsulation of how these jewels connect us to a different time, place and person. This item is a vinaigrette case and is layered in both sentiment and purpose. Through […]

Read More

Objects are important as they tell our human history by connecting us to past places and people. These tangible bonds offer us the rare opportunity to touch history. Never has this sentiment rung truer than in the instance of this imperial half pint measuring cup. One of the humbler items in the Kalmar's collection, although […]

Read More

To kickstart The Kalmar Vault series we begin with two significant pieces of Australian jewellery history. From the Kalmar's private collection comes a fantastic pocket watch and Albert chain from acclaimed jeweller and watchmaker, Mr. Henry F Hutton. "The business founded by Henry Hutton around 1880 became one of the premier retail jewellery establishments in […]

Read More